The hammer is but one tool: using theory to transform restorative approaches in schools

Part 2 of 2

“If the only tool one has is a hammer, then one is in danger of treating everything as if it were a nail” – Abraham Maslow

Part one of this article discussed the need for professional learning in the field of Restorative Practice to encompass theoretical models, specifically Affect Script Psychology (ASP) (Tomkins, 1962) so that teacher learning moves from the ‘what’ of restorative work (practical strategies) to the ‘why’ (values based). Without emphasis on the theory, schools are at risk of applying restorative approaches to misdeeds and conflict only – the hammer and nail so to speak. The philosophical and theoretical underpinnings of Restorative Justice [Practice] are more complex and encompassing than a simple behaviour management tool.

Part one outlined the impact of affect shame and presented an example of shame at work in an academic setting – the math lesson. In Part two we will again look at this theory in the context of the real world by examining how ASP plays out for students and teachers involved in a restorative approach to conflict. Affect Script Psychology describes that we humans are born with 9 innate affects that instruct us about what to pay attention to and is a primary motivator for our thoughts and behaviour. We experience biological and physiological reactions to various stimuli in our environment and within our relationships with others (the affects) and as we progress through life, our experiences, interpretations and memories of events create our unique personalities (scripts).

As a reminder, affects are either positive (inherently rewarding), negative (inherently punishing) or neutral (neither rewarding or punishing). The positive affects, according to Tomkins are interest – excitement and enjoyment – joy. The neutral affect is surprise – startle. The negative affects are anger – rage, distress – anguish, fear – terror, dissmell, disgust and shame-humiliation. Further information can be sourced at www.tomkins.org. We are happiest and healthiest when we can maximise positive affect, minimise negative affect and minimise the inhibition of affect. The more life experience we have the less likely we are to observe pure, innate affect as our scripts are played out very quickly after exposure to a trigger.

Affect shame and its subsequent script formation is of high interest in restorative work. Remember that the role of shame affect is to let us know that positive affect has been interrupted, that something went wrong and motivates us to fix it. This is especially important in our relationships with others as humans are social beings and rely heavily on social connection for survival. If we weren’t motivated to fix broken connections, we would suffer. Positive relationships are a foundational principle of Restorative Practices; we seek to build relationships and recognise that when mistakes are made, relationships are damaged and require repair. It is highly beneficial for educators then to be adept at spotting affect, especially affect shame, and to approach students accordingly.

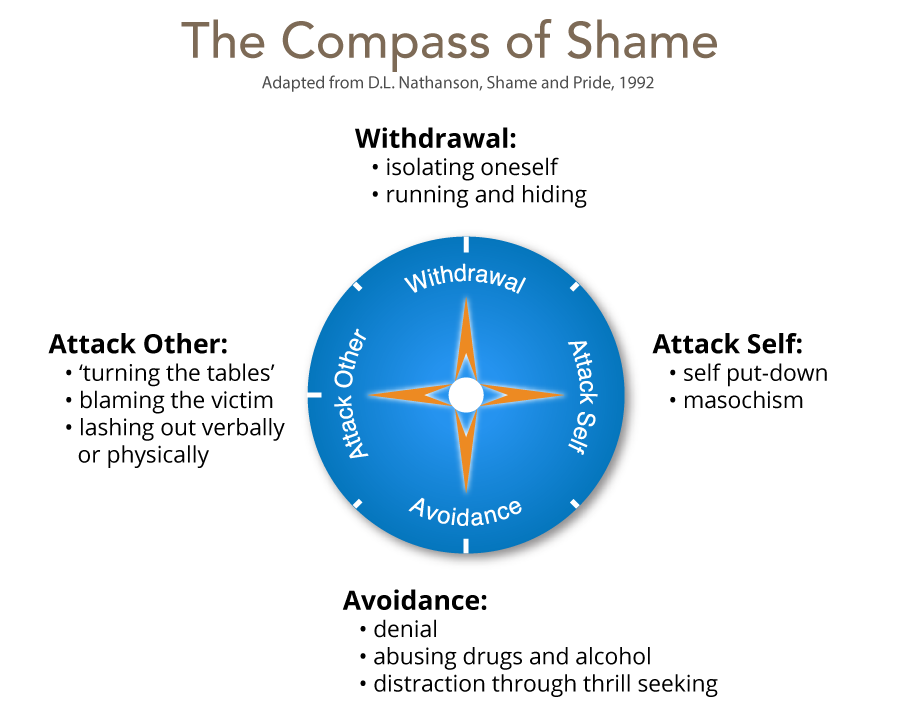

The physiological responses of affect shame include averting one’s eyes, a blush to the cheeks, slumping of the neck (biochemical muscular response) and a cognitive blockage. When we become aware of experiencing these bodily symptoms, we begin to scan our memory for similar experiences in the hope of knowing how to respond and how to stop this terrible feeling. We can respond adaptively or maladaptively to shame. An adaptive response might look like accepting that we feel terrible, soothing our self, acknowledging a mistake was made, attempt to fix it and hopefully learn from it. Unfortunately, this is not so easy to do. Donald Nathanson describes four maladaptive responses to shame which he presents on the Compass of Shame (1992).

He suggests we turn to one or more of these behaviours in order to ignore, reduce or displace shame. Unfortunately, none of these behaviours require us to examine or address the behaviour that led to experiencing shame in the first place thereby increasing the likelihood that it will happen again. Restorative approaches teach and support people to look at the behaviour, separate from the person, and address it as a learning moment – ‘what is it that I can learn from this?’.

The following example demonstrates how an understanding of Affect Script Psychology can positively impact student/teacher and student/student interactions when wrongdoing occurs.

Student A overheard Student B speaking about her disrespectfully to another student. Student A approached Student B and threatened to share personal information if she didn’t stop. After noticing the absence of Student B, the Teacher investigates and is informed of the situation from their peers. This teacher has been trained in ASP and understands that Student B is experiencing shame and distress affect and that her maladaptive response to shame is to withdraw. The teacher will have to support Student B to metabolise her shame which is done by asking questions about how they feel, who is affected by what happened, how they can make things right, what support they might need to make amends and how to manage future situations that trigger shame.

| Student | Trigger | Possible Affect/s | Behavioural Script | Teacher Response |

| A | Spoken about disrespectfully | DistressAnger

Shame |

‘fight’ – threatening behavioursPower plays

Invading physical space |

1. Speak with both students individually to get the story (to identify affect present)2. Invite both students into a restorative conversation together (seeking to trigger affect interest in sorting the problem out)

3. Prepare students for the restorative chat (this goes a long way to metabolising negative affect) 4. Facilitate a restorative dialogue between students, closely observing affect changes 5. Support students in the creation and negotiation of consequences/making amends 6. Discuss shame responses with students individually to assist them in identifying maladaptive scripts and seek to develop adaptive scripts 7. Follow up with students after a period to check in on the relationship and reinforce adaptive behaviour scripts |

| B | Verbally threatened | ShameFear

Distress |

‘flee’ – leaves the environmentAvoids Student A

Is absent from school Misses classes Does not engage with friends Avoids social media |

Table 1.0 Responding to wrongdoing by applying knowledge of ASP

The educator who receives a basic level of restorative training, that which does not include ASP content, may have handled the situation differently. From the outside they may approach it similarly: the students would be invited to attend a restorative chat which would have been warmly conducted according to a scripted dialogue. The students may have taken responsibility for their actions, agreed on a way to make amends and move forward and may have even apologised to each other. A band-aid has been used to cover up the immediate harm, but the underlying issues remain. What is lost is the opportunity to collaboratively examine the behavioural responses of both students along with an opportunity to impact maladaptive scripts and prevent the conflict, and responses to it, from occurring again. A huge gripe of teachers is re-offending – the same students presenting with the same challenging behaviours time and time again. Wouldn’t it be great if we could impact this in some way? Restorative approaches will make an impact, but only if we get the teacher education right.

Professional development in this field must seek to explore a broader conceptualisation of Restorative Practice that shifts understanding from strategy to theory. If schools are to be successful at not just implementing but sustaining restorative approaches, educators must understand the role of Affect Script Psychology in human behaviour, particularly the powerful motivator – shame. We must shift our attention away from the conflict or misdemeanour and seek the teaching and learning moment within. For it is only when we seek to understand the motivation behind behaviour that we recognise not every behaviour is a nail to be hammered.

We would love to hear your thoughts on this two-part article so be sure to comment below.

Add A Comment